“The beginning of the new is already there in everything,” is how consultants Iain Kerr and Jason Frasca explained innovation at a recent Agile to agility Conference. “It just needs to be actively and experimentally co-opted.”

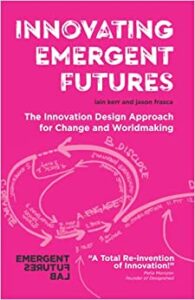

As co-directors of the MIX Lab at Montclair State University, Iain and Jason began working together to foster innovation at the university level, and in 2018 they formed the Emergent Futures Lab to share their approach with public and private organizations. They’ve since published their findings in the book Innovating Emergent Futures – The Innovation Design Approach for Change and Worldmaking and on the Emergent Futures Lab website.

To learn more about their unique approach to innovation, we asked Iain and Jason how they help individuals and agencies engage with their environments to find unintended possibilities in current realities. The secret, they say, is to release the myth of the lone genius and create an environment where teams can experiment and collaborate.

How can we all be innovators?

Iain: We like to say, “Don’t be a leader, be a follower.” Follow the unintended, the novel, the possible, and collaborate with it. The key role people play in innovation is being able to sense something novel emerging, and then experimentally follow and stabilize it.

The traditional heroic role of geniuses who come up with an idea by themselves in their head and fight to make it real is a fiction we tell ourselves.

Why is the heroic genius a fiction?

Jason: The individual hero’s journey Iain is referring to is usually a revisionist history re-written after the fact. People don’t understand what creativity is, so they call it “ideas.” We have this fallacy of the genius, the one singular person who comes up with an idea. The media feeds into it, because that will get clicks, and we have this fiction of the individual overnight success. In reality, there’s no such thing as the heroic individual or an overnight success. It can be 20 years or more of work that’s taken place by many individuals prior to the moment when the person appeared on your screen as an overnight success. Their success has been building not just because of their work, but because of all of the collaborations and events and tools that they have engaged with to get to that point.

Iain: The microwave was someone working on an early version of radar who had a chocolate bar in their pocket and the radar device melted the chocolate bar and it started them on a journey of how to use radar to warm food. Viagra was a heart medicine with the unintended capacity of changing male anatomy in interesting ways, and it turned out there was a lot more money in that. Penicillin came from leaving petri dishes out during a holiday and coming back to find mold growing on them. At the time, Alexander Fleming didn’t think it was groundbreaking, in fact it took 30 years to develop the antibiotic.

If you look at any overnight success story, at what actually happened, not what people say about it, you find many different examples not of ideation, but of exaptation, which is developing something unintended from what was already in existence.

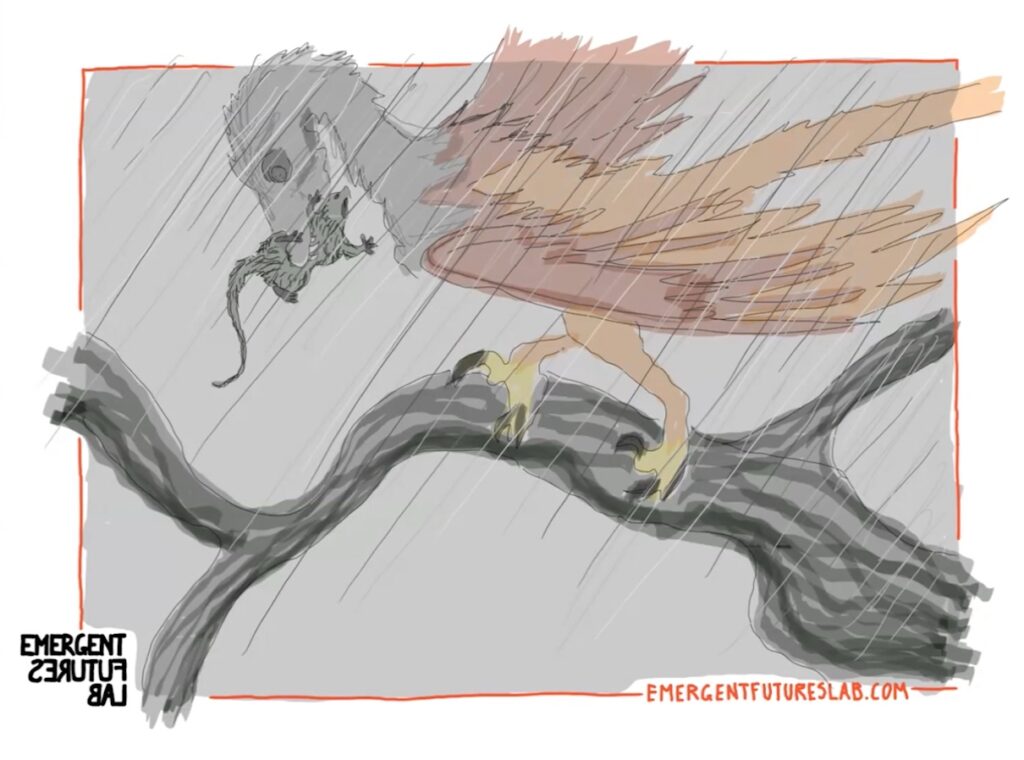

How is the dinosaur wing an example of exaptation?

Iain: Darwin realized that If there was no God to ideate and create a wing, then the wing already had to be in existence before it got co-opted for flight. He found that the wing started off as a scale, and the scale had the unintended possibility of growing to be like a feather and keeping dinosaurs warm. Feathers could hold pigment and look sexy, so feathers get really big really fast, and grow wherever they don’t get in the way, like under the arms. Eventually a dinosaur falls off a tree and the feathers under the arms have the unintended capacity of allowing the dinosaur to glide to the ground and not die.

This turns out to be true of human innovations as well. All human innovations involve discovering something unintended. Or pushing a system in a way that was unintended.

What is your innovation process?

Iain: Innovation should come through doing. That’s why we call it co-emergence. You want to discover the innovation through use, instead of coming up with the innovation and seeing if it actually works. In the dinosaur example, you don’t find the unintended use of feathers by looking at them or thinking about them, you find it when you fall off a tree and not die.

When you have an innovation process, you don’t have to bring geniuses into the room. With the right processes, people can experiment and develop and work collectively and do astonishing things.

The Innovation Design Approach guides companies through a series of tasks to harness their strengths to discover new opportunities not previously considered.

Where do you start?

Jason: First you need to engage and disclose to understand what exists. You can’t disrupt something if you don’t know what exists, you will just regurgitate something new to you, but not necessarily new to the world. So the only way we can leave the known behind is to understand what it is and block it. The more disruptive we want to be, the more primary elements of what exists are blocked so we can follow opportunities that are novel or lead to more novelty.

The goal isn’t to prove what works, but to see what new things emerge and start to follow those things and collaborate with them. We ask, “What would happen if we did this?”

Innovation is long, slow, and hard and there’s no way to guarantee an outcome. But that’s the reality of innovation. You have to experiment, you have to do it, you can’t just place a pin in a map and find it.

What can agencies do to be more innovative?

Jason: For a team, provide a process that can be followed by anybody so everyone can participate in the overall ethos and ecosystem. It democratizes your community and allows everyone to be creative and innovative, rather than one genius who comes up with ideas for everyone to follow.

Iain: For a person, try to stop doing the things you most standardly do.

Figure out the 10 most common things you do every day and block them. Unintended capacities will start to happen.

Just be curious, lean into those. You’ve got to trust the process and not decide in advance that nothing interesting will come out of it. (See 22 Ways to be More Creative and Innovative in 2022.)

Jason: “Keep your difference alive,” is what we like to say. Own it.

How do you help clients with this process?

Jason: We worked with a large transit operator who selected 20 rising stars from 20 departments to work with us over eight Fridays for eight hours, basically two weeks broken up over two months.

Iain: This was a regional rail service moving millions of people a day.

We got them to go out and look in the system to find what unintended things were happening and to pay attention to the affordances, the unintended possibilities that people were picking up in the system.

When they actually got into the environment where people sit, they found that the closer people got to their destination, the less they occupied seats and the more they stood near the door to get out quickly. The team realized they needed pockets for standing, not more seating. The problem they needed to invent was standing space, not how to get as many seats as possible into the trains. So they had the wrong problem and they had to experimentally invent the right one.

Why is your approach unique?

Iain: Most innovation consultants will have you brainstorm your way to novelty. They might dress this up with techniques from trend analysis, futurism, or design thinking, but if you look closely at the heart of all of these methods, it’s always a version of “get creative people in a room and facilitate their brainstorming.” This is an industry fallacy — really a cultural fallacy.

Ideation is not innovation. If you can think and ideate a solution, then it already exists. If it exists, your competition is working on it.

The truth about how to innovate is harder to explain and harder to accept, for it goes against so many deeply held cultural beliefs: radical transformative and paradigmatic innovation is not about grand ideation.

How do existing companies under threat survive in these challenging times? Either pivot existing products and services to unintended possibilities or develop new innovative solutions.

Where can we join your innovation discussions?

We use LinkedIn to catalyze ongoing discussions in regards to creativity and innovation.

We both post daily to stimulate dialogue around the two questions that drive our work: What is innovation? And how do we innovate?

We encourage readers to follow us and join in the conversation:

Learn more

- Sign up for the Emergent Futures Lab newsletter

- Buy the book, Innovating Emergent Futures – The Innovation Design Approach for Change and Worldmaking

- Contact us to learn how to bring more innovation to the public sector